Out there, it’s different

18.08.2021

It is not uncommon for the German name of the IASS to evoke confused looks on people’s faces: Institut für transformative Nachhaltigkeitsforschung – “I’m sorry, but what is ‘transformative’ supposed to mean, and what is ‘transformative research’?” A comprehensive yet straightforward answer is given in Jan Freihardt’s book “Draußen ist es anders” (“Out there, it’s different”), subtitled “Treading new paths towards a science of transition”.

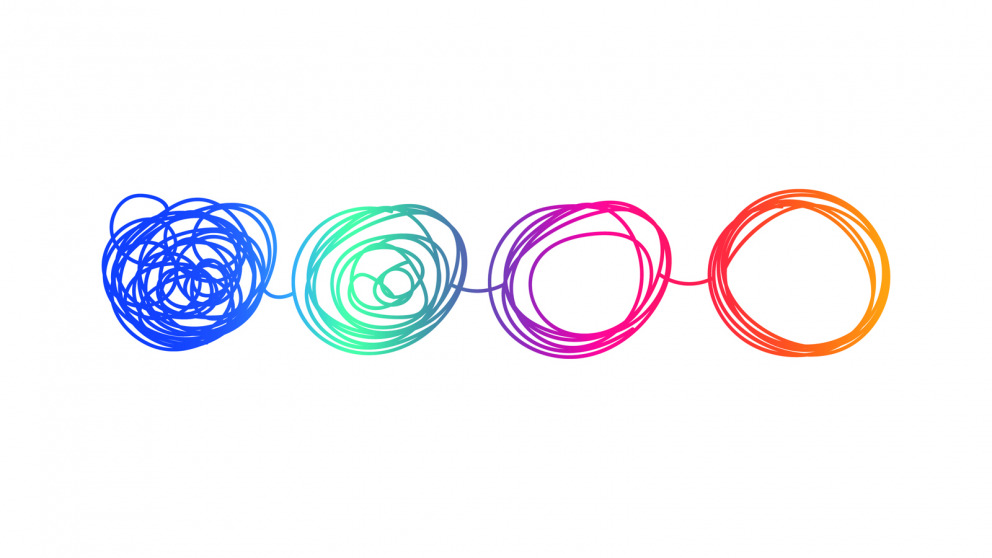

The point of departure of the book, as well as the idea of transformative science in general, is the assessment that the world is at a crossroads: we are caught up in multiple crises because humanity has run up against various planetary boundaries, resulting in ecological, social, and economic harms. Freihardt presents several related debates – for instance the debate around growth (growth, de-growth, or green growth?) – and comes to the conclusion that the “Great Transformation” demanded by the German Advisory Board on Global Change “is a societal discussion as to what kind of world we want to live in, and how we want to leave this world for our children”.

Values, attitudes and convictions play an essential role in this discussion. Science should not simply deliver facts, but rather take up ethical issues, overcome disciplinary borders and integrate non-scientific perspectives as well. Freihardt argues that transformative science brings society’s various bodies of knowledge together and works as a “catalyst for societal processes of change” (Uwe Schneidewind et al.). In doing so, he refers to Ortwin Renn, who advocates for a kind of “catalytic science” which “assembles the relevant knowledge from science and other sources of knowledge for a given issue and preparing them for public debate”. In other words, transformative science should not replace “classical science”, but rather complement it.

“Basically, the point of transformative science, which actively weighs in on social-ecological transformations, is to reorient the relations of science and society”, Freihardt summarises. Consequently, it must embrace transdisciplinarity by including knowledge and actors from outside academia in research. Scientists should thus learn how to communicate with non-academic target groups, who especially ask, “what for” and “to what ends”. Classical science, on the other hand, mainly just deals with the “what”. Scientific communication therefore plays an important role in transformative science.

Science today

The book describes in a nutshell the contemporary state and development of the scientific system, sheds light on the balancing act between promoting science and scientific freedom and delves into the difficulties that transdisciplinary and transformative science runs into in this arena. Indeed, the ruling reputation system is geared towards peer-reviewed academic publications, and these are usually classified according to individual disciplines. Furthermore, he concludes that the idea that “science delivers facts, policymakers and society act” is too one-dimensional.

The author rightly asks whether this kind of linear model does not fall too short but remains true to his – transformative – scientific perspective. Even the demand of “Fridays for Future” that policymakers should “follow the science” in order to halt climate change fails to capture the complexity of the reciprocal relations and influences between science and society, he argues. Academic communication, as Freihardt writes, should not be a one-way street.

Exactly, neither in one nor the other direction. Indeed, the non-academic perspective, so elementary for transformative science, is a bit lacking in “Draußen ist es anders”.

A good, understandable overview

“Draußen ist es anders” does however deliver a good and understandable overview of transformative science and research. It presents the three intersections of transformative science between science on the one hand, and policy, civil society and economy on the other. Moreover, the book deals with the growing area of “Citizen Science” and pleads for greater investment in education for sustainable development. Indeed, transformative science demands different competencies than are currently taught at institutions of higher education: beyond knowledge of facts and systems, students need to acquire knowledge about processes and learn how to shape these processes, in addition to learning how to apply the knowledge they have gained.

The book is convincing not least because of its examples, quotes and interviews with actors involved in transformative science – including IASS scientists – that help to illustrate and clarify the subject matter. Each chapter is introduced by several leading questions and at the end there is a short summary for the reader. This structure accommodates our reading habits, characterised as they are by websites and the linking of different content. The fact that the author manages to keep track of his argument demonstrates how intensively Freihardt has dealt with the topic.

To conclude, the book introduces several “pioneers of change”, as Freihardt calls them. These interviews, fact sheets and – of course – QR codes for each of the websites, not only make the book valuable for anyone who has always wanted to know what exactly “transformative science” is, but also make it a reference for anyone who would like to embark on new paths towards a science of transition.

Jan Freihardt

Draußen ist es anders

Auf neuen Wegen zu einer Wissenschaft für den Wandel

Oekom-Verlag, München, 2021, 252 Seiten