Raising Revenue with Attractive City Planning

08.09.2021

Local retail profits from the mobility transition and should advocate it.

When a cycle path or a car-free zone is set to be created in German city centres, it usually doesn’t take long for a photo of an angry (almost always male) retailer to appear in the newspaper. With his arms crossed and an angry look on his face, he warns of the impending “apocalypse” for local shops because of reduced parking. The newspaper reports it under the heading “Downfall of retail”, and established business associations see “the end of many city centre retailers” coming.

Yet, on the contrary: a study carried out at IASS Potsdam shows that in two selected shopping streets, only 6.6% of the people used their car to go shopping. That means, the overwhelming majority of them – 93.4% – didn’t get there by car. 91% of the money that customers left in local shops came from the pockets of customers who came by foot, with their bike or with public transport. Those who do use their car to go shopping in the city are only responsible for 8.7% of revenue.

This is no surprise. It corresponds with studies that appeared in 2019 on the city centres of Offenbach, Gera, Erfurt, Weimar and Leipzig. In fact, research about mobility and the local economy from other European countries, North America and Australia has come to the same result. In Australia, researchers calculated that one square meter of parking brings in $6, while a square meter of bike racks generates $31.

Subjective view of retail

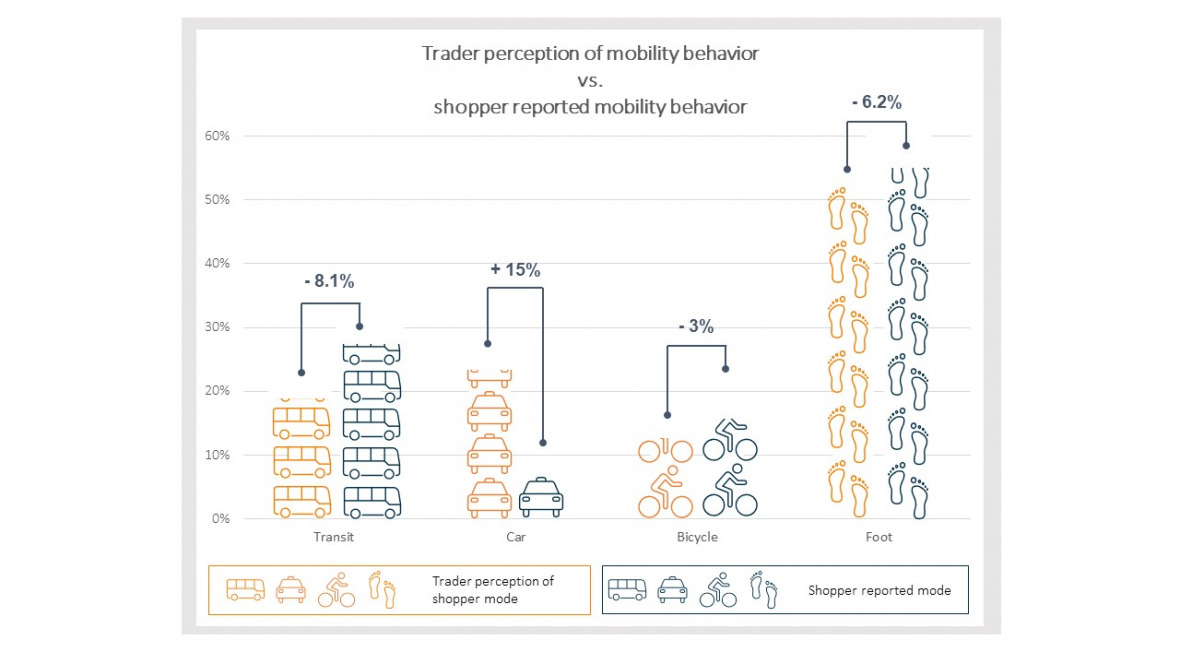

Retailers’ preference for cars is understandable. Business owners often transport goods, and a car is useful for that. While, as mentioned above, only 6.6% of customers get to the store by car, that figure jumps to 42.1% for shopkeepers. Moreover, retailers tend to generalise their own behaviour: the cycling shopkeeper thinks that her customers cycle more than they actually do, and the car-driving shop owner overestimates the number of his customers who drive to his store.

Yet to best represent the interests of local business, organised business associations like the Industrie- und Handelskammer (Chamber of Commerce and Industry) shouldn’t rely on their instinct, but rather weigh advantages and disadvantages for economic actors based on facts. Policymakers and administration often listen closely when economic actors voice their opinions on city restructuring. If business rejects cycle paths or car-free zones, the chances that they will be created diminish dramatically. All too often, this prevents urban transformation.

Lively city centres bring purchasing power

Indeed, what often happens is that with more sustainable and people-friendly infrastructure, more room, less noise and better air, city centres blossom. Retail revenue increases because appealing places attract purchasing power. Getting some advice in the shop, random chit-chat, tasty snacks and casual purchases along the way are what make our city centres attractive – not being able to park our car in them. Appealing window displays entice (potential) customers who are strolling by or riding along on their bikes. The same doesn’t apply to people in their cars.

Local business also profits indirectly when city centres are no longer fixated on cars. Instead of leaving their money at the petrol station or car dealer – where it then usually goes directly into pockets far away – citizens can spend it on a walk through the city centre.

Promoting climate protection and sustainability

Naturally, it’s also a question of sustainability. It is well known that the transport sector is a problem child of German environmental and climate strategy. According to a recent judgement by the European Court of Justice, Germany has “systematically and persistently exceeded the limits for nitrogen dioxide” in 26 municipalities. And the transport sector has done extraordinarily little to reach climate goals in the past.

What is more: walking and cycling keep you fit and reduce health care costs. If the temporary cycle paths that were created during the corona pandemic in some European cities remain, up to $7 billion could be saved on health care costs, according to a current study from the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change.

Taking all of this into account, urban retail should enthusiastically call for restructuring city centres in favour of sustainable transport and the long-term reduction of traffic. More restructuring is possible and could generate more turnover. Not only that, the climate-friendly transformation of our mobility offers the chance to establish lively, attractive, and economically sound centres in our towns. Local economic actors can contribute by getting involved in debates on sustainable city planning and advocating better infrastructure for pedestrians, cyclists, and public transport. Their voices carry a lot of weight in the media and politics.

This article was first published in German by Forum Nachhaltig Wirtschaften (8 September, 2021).