The Ocean at COP26 - “Ocean Action is Climate Action”

17.12.2021

The close interlinkages between climate and ocean, and the large-scale and far-reaching effects that changes within this nexus have on humanity, have received growing political attention during the past years. The UNFCCC Climate Conference in 2019 (COP25), which was hosted jointly by two States with large ocean spaces, Chile and Spain, is known as the “Blue COP” as it emphasized the importance of the ocean for climate action. Efforts to meaningfully include the ocean in global climate governance culminated at the “Ocean and Climate Change Dialogue” mandated by COP25, which took place online during the height of the pandemic in late 2020.

The recent COP26, which took place in Glasgow in November 2021, offered a promising opportunity to maintain momentum and enhance initiative for ocean-based climate action. In the run-up to the conference, prominent NGOs and research organizations published recommendations for the integration of the ocean into UNFCCC processes and engagements.

On the opening day of COP26, the Because the Ocean Initiative launched a declaration demanding an “ambitious ocean outcome at COP26” to fight climate change, preserve biodiversity, and protect the ocean. This third declaration of its kind since COP21 in 2015 was signed and acknowledged by many world leaders. During the conference, on the floor and in the virtual realm, ocean representation was high, with a broad range of events, including events held at the IOC-UNESCO co-organized COP 26 Virtual Ocean Pavilion, where many fruitful discussions were held such as the “Roundtable on the UNFCCC Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA) Ocean & Climate Change Dialogue”. The COP26 Ocean Action Day (November 5, 2021) had high-level representatives speak on and make pledges for ocean-climate-action at a ministerial event organised as part of the official UNFCCC Presidency Programme.

The question of whether the ocean belongs in climate conversations was finally settled at COP26. However, it was at side events on-site and in virtual spaces outside of the official UNFCCC Presidency Programme that the ocean was most widely discussed. As United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the Ocean Peter Thomson noted in an open letter to Patricia Espinosa, Executive Secretary of the UNFCCC, which he delivered at an event in the Commonwealth Pavilion: “The UNFCCC process needs a decision text that recognizes the intrinsic linking of the ocean and climate change and calls for stronger action by parties.”

One ocean, many faces and voices – and opportunities

The ocean was part of many narratives over the course of the COP26 in Glasgow. For one, the ocean was recognised as one of the significant victims of climate change, as the effects of ocean warming, sea-level rise, acidification, or deoxygenation undermine ecosystem functions, disrupt species migration and have many other detrimental consequences for the ocean and planet. In his opening statement, the Prime Minister of Fiji Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama urged that “the science is clear, no […] ecosystem will be spared from the reckoning that lies beyond 1.5°C of warming, including our oceans, the lungs of the planet.” But especially the climate change-related effect of sea-level rise makes the ocean not only a casualty of a changing climate, but also a threat to low-lying coastal communities, whose livelihoods and lives are threatened at a compromise for less ambitious climate targets. The Prime Minister of Jamaica Andrew Michael Holness urged that “meeting the 1.5 target [is] a matter of life and death” for the Caribbean island nation. Small island States are among those fearing most the consequences of climate change. At COP26, an alliance of island nations stood up and pushed for more ambition and action to reach global climate targets and greater support for countries grappling with the effects of climate change. Among them was Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados, who delivered a captivating speech at the COP26 opening ceremony, and the Foreign Minister of Tuvalu, Simon Kofe, who chose to add more weight to his words by giving his speech standing in knee-deep ocean waters.

But it was also recognised at COP26 that the ocean should play a more significant role in climate action. The ocean’s potential for carbon sequestration provides an opportunity for climate action – a fact that was discussed widely during COP26. As Lord Zac Goldsmith, Minister for Pacific and the Environment of the United Kingdom, stated on Ocean Action Day at COP26: “We cannot tackle climate change without the ocean”. According to a special report commissioned in 2019 by the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy, ocean-based solutions could close the global emission gap by 21%. At COP26, blue carbon ecosystems such as mangrove forests were determined by the climate community as part of the solution to climate change, with the potential to provide multiple benefits (such as reducing coastal flooding) while storing carbon. As Andrea Meza, Minister of Environment of Costa Rica stated, “[b]lue carbon must be part of our action towards climate neutrality”. However, as global temperatures rise and ocean temperatures with it, valuable ecosystem functions and services of the ocean and coasts are lost - among them the potential to remove carbon from the atmosphere.

Beyond such “natural” options that aim to restore and conserve marine and coastal carbon-capturing ecosystems, more technical ocean-based approaches to climate mitigation were also discussed and presented at COP26. Marine carbon dioxide removal techniques such as ocean alkalinization are currently still at the research and testing stage, and their potentials, benefits and risks are the subject of debate. But discussions at a panel hosted by the World Ocean Council on “Ocean carbon removal, from technologies to industries” also showed that there is broad interest in these technologies from industry and the business community. Other approaches to ocean-based climate action are linked to sustainable ocean economies that ultimately lead to emission reductions. Catarina Martins, Chief Sustainability and Technology Officer at MOWI and member of the SeaBOS Task Forces, highlighted the potential of sustainable ocean economies and spoke of the integration of macroalgae into our food systems, stating that “[b]lue foods are a fantastic solution for climate change”.

Persisting gaps for synergistic ocean and climate change action

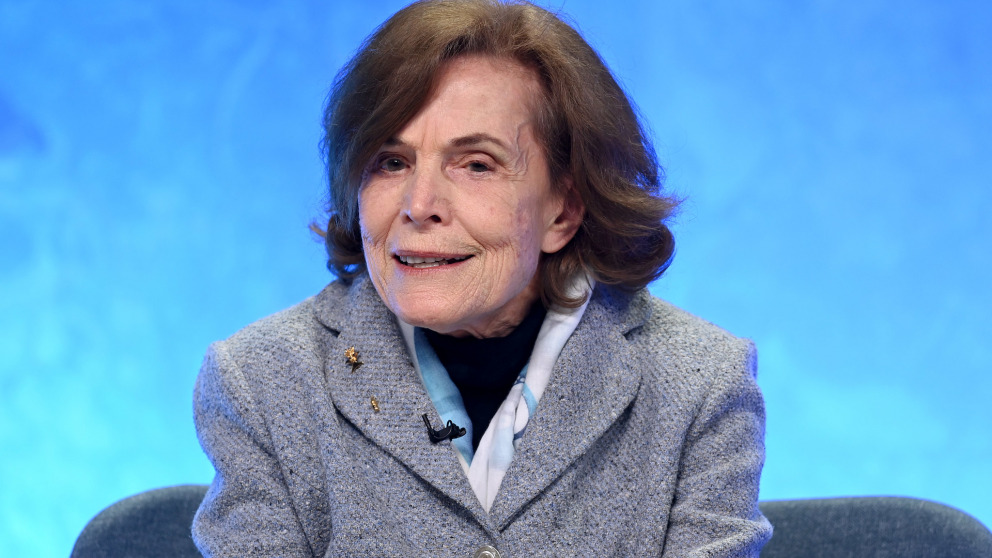

In an emotional opening speech at the Ocean Action Ministerial Event on 5 November 2021, the now retired ocean science pioneer Sylvia Earle admonished: “We are the agents of change, and we can change in a positive way, as well as in a negative way”. The urgency of the climate problem and the inextricable link between climate and ocean was emphasised during all the various panels that brought together high-level speakers and participants from politics, science, NGOS, the business community and philanthropic organisations to discuss possible solutions, highlight good practices and deliver commitments for action. Belize, for example, with support from The Nature Conservancy, the U.S.A. and Credit Suisse engaged in a novel dept-swap model, committing to annual spendings of $4 million and providing $23 million for a marine conservation trust to protect and restore a coral reef that is described as the world’s second largest after the Great Barrier Reef.

But despite observable progress and the anchoring of “the ocean in the climate pact”, including the establishment of an annual dialogue on ocean action, more tangible commitments for both climate and the ocean are needed to ensure measurable progress. While the interdependence between ocean action and climate action was explicitly noted throughout talks at COP26, ocean experts and officials have highlighted several factors that are likely to hinder the practical implementation of this notion. These include the following:

- Ocean policy and governance for climate action is still emerging: While some progress has been made towards integrating ocean solutions into UNFCCC processes, numerous barriers persist. Many blue carbon ecosystems are not yet included in UNFCCC carbon mechanisms such as REDD+ or the Clean Development Mechanism, making the leap for individual countries to include blue carbon projects as part of their mitigation or adaptation strategy an inconvenient one. At the Ocean Pavilion Roundtable on the UNFCCC SBSTA Ocean & Climate Change Dialogue, Vladimir Ryabinin of UNESCO noted that not enough countries even have the right governance structures in place to comprehensively reflect the role of the ocean in climate action, as many countries still lack “Ministries of the Sea”. Andrea Meza, Minister of Environment of Costa Rica, also noted the increasing difficulty of governing ocean-based solutions for climate change within mandated policy silos.

- Ocean-based climate solutions lack funding, strong leadership, and meaningful partnerships: The burden of pursing ocean-based climate action falls largely to island states. It is these countries that are experiencing the worst effects of climate change, even though the lion’s share of excess carbon was emitted by developed nations. COP26 made it clear that the funding stream from main emitters to these ocean-based economies is not where it ought to be. Indeed, as Prime Minister of Barbardos Mia Mottley noted at COP26’s opening session, donors have failed to deliver on climate finance commitments. At the Ocean Pavilion Roundtable on the UNFCCC SBSTA Ocean & Climate Change Dialogue, Joanna Post of UNFCCC offered that financing that unlocks the co-benefits of ocean-based climate action, e.g., adaptation benefits, could simultaneously enhance climate mitigating features. Funding alone, however, will not enable ocean nations to implement blue carbon ecosystems over the longer term. At the Ocean Pavilion Side Event “Ocean & Adaptation, Resilience, and Mitigation”, Angelique Pouponneau of SeyCCAT, the Seychelles Conservation and Climate Adaptation Trust, explained that what is needed are meaningful partnerships between the Global North and South rather than one-way capacity building and “parachute science”. She urged, “solutions are not solutions if they are not equitable and just”.

- Ocean science to steer ocean & climate action: Another main message from COP26 for the comprehensive integration of the ocean into climate action was that ocean science and monitoring systems should be better utilized in decision-making processes. Current climate targets fail to adequately account for the role of the ocean in the regulation of the climate. At the Science Pavilion Side Event “Tracking Ocean Climate Change and Impacts on our fragile Ocean”, Anya Waite, co-chair of the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), noted that the under-observation of the ocean is allowing climate models to fail. As GOOS is not mandated by an international organization like the Global Observing System of the World Meteorological Organization, funding streams are uneven, causing large gaps in ocean observations time series and data, and carbon sequestration is often not measured as a result. Anya Waite urged that “policymakers need to understand that their trillion-dollar investments in getting to climate targets will be unsuccessful without the less than billion dollars it will take to bring the ocean observation system to the state it needs to be.” In addition, GOOS is working on the integration of “informal” ocean observation via indigenous voices into regional observing systems.

After COP26, NGOs criticised that while the ocean took centre-stage in the UNFCCC processes on climate mitigation, adaptation, and finance, the outcomes achieved were still not ambitious enough to halt global warming. Stepping up ambition in ocean-climate action alone will not put the 1.5˚C target within reach. Ensuring that commitments translate into effective action requires that we address gaps in fields that might seem less urgent, such as ocean policy and governance, or ocean science. Then, we will be able to be, as Sylvia Earle suggests, “agents of change […] in a positive way”.