Turning debt into climate action: A Global South approach to the climate struggle

17.10.2022

This year has made it abundantly clear that we are edging closer to climate catastrophe much faster than previously thought. Floods, heatwaves and wildfires across the globe have cost thousands of lives and destroyed the livelihoods of millions more. At the same time, global cooperation on climate change remains lacking. To the contrary, confronted with a steep rise in energy prices, as a result of an unexpected worldwide squeeze on energy supplies over the past year, Global North governments are undermining their own carbon emission reduction targets. For example, many countries have turned to coal, nuclear power, and shale gas in response to the crisis. This revival of fossil fuels is especially unjust for countries in the Global South, where large swaths of the population do not even have access to a stable energy supply.

One major obstacle for Global South countries are rising public debts. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), more than half of the poorest countries in the world are effectively bankrupt or just a step away. The Covid-19 pandemic, rising food and energy prices and interest rate increases driven by the US dollar are driving the poorest countries of the world into a debt spiral. Confronted by rising deficits, they are forced to continue to extract their last resources in order to fulfil the demands of their creditors.

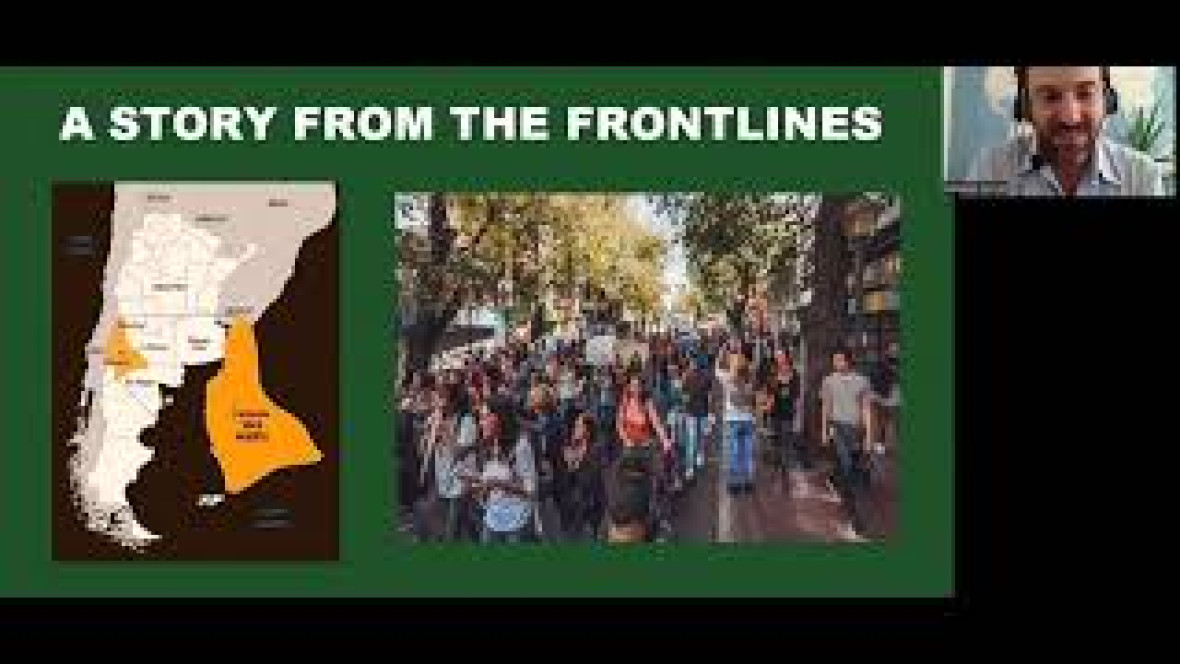

The Debt for Climate movement is tackling this problem by demanding the complete cancellation of the debts of countries in the Global South. Esteban Servat, one of the movement’s leading activists, was our guest for the August session of the Justice in Sustainability lecture series. Born in Argentina, he worked for biotechnology companies in Silicon Valley for around 10 years. After becoming disillusioned with the realities of the private health industry, he returned to his home country to start a multicultural, regenerative ecovillage. However, he had to leave the country after denouncing fracking and mega-mining in his native province of Vaca Muerta, Mendoza.

Media

Esteban Servat: Climate Crisis Activism from a Southern Perspective

Now based in Berlin, it is against this background that Esteban traced the colonial roots of the global debt system: “The plundering of the Global South was first pursued through invasions and armies but today and since the 20th century it is mostly achieved through debt”. As he said in the lecture, “The climate debt is not just about carbon emissions and methane emissions. Climate debt is also about addressing the reparations for loss and damage that are owed to the Global South as a result of 500 years of exploitation, colonization and enslavement of much of the world.” The Global North is overrepresented in institutions like the World Bank and the IMF. With the Global North accounting for most historical carbon emissions and the Global South bearing the brunt of the climate crisis, there is also an ecological debt owing. As Esteban said, “There is no way that any country of the Global South could afford any energy transition while we are paying 50 to 80 cents of every dollar we make to the IMF or the World Bank in a mechanism of colonialism known as ‘debt trap diplomacy’.”

Esteban noted that the Debt for Climate campaign allows different social movements to rally around a common platform. One obstacle he observes in the global climate movement is the lack of leverage on policymakers since environmental issues are often pushed by disadvantaged groups like youth or indigenous communities. Esteban claimed, “We need the workers not only because there is no climate justice without social justice but also because the workers of the world are the experts in class struggles.” The Debt for Climate campaign shows how the climate movement can connect with the working-class movement and unions, who have an interest in changing the predominant economic policies as well as the means to do so by organizing strikes and mass protests. “That capacity to organize and unionize is exactly what allows them – whenever they have to fight for their rights or their salaries – to paralyze an economy,” Esteban pointed out, adding, “By connecting debt and climate we have been able to bring thousands of workers onto the streets.”

While this strategy might be successful in the Global South, it is unclear how far the working class in the Global North will rally around common goals with the climate movement. As Esteban said during his lecture: The debt for climate campaign is a “south-centric” movement. “Uniting the Global South and the Global North, we can deliver the change that we need in order to bring some justice into the climate justice agenda,” Esteban said. Nonetheless, the appeal of the Debt for Climate movement lies in its proposal of a clear strategy to effectively challenge the status quo in times when many have given up hope that politics can be a real tool in staving off climate change, and climate activism and grassroot movements seem to have come to a dead end. “It is urgent that we break out of the bubble of climate activism,” he warned. “This is about turning debt into climate action.”

While the Fridays for Future movement was able to mobilise millions, their demands were largely ignored by world leaders. What is often missing in climate activism is a theory of change, that is, how protests can be translated in actual political change. The Debt for Climate movement raises the question of where real political power lies. As Esteban said, “We cannot allow this injustice to continue. We cannot allow the Global North governments to pretend to be blind to the reality that they enforce every day. They have the power to cancel debt, they have the power to lift the knee off the neck of the Global South.”