Hidden Ghosts: A Story of Climate Devastation

23.01.2023

Let's close our eyes for a moment and travel back in time to childhood. Try to remember a time when you felt scared or devastated, the feeling of losing someone you truly love. And now, let’s imagine that these moments begin to multiply and persist. They stay in our minds for days and weeks.

For many of us, what keeps our memories alive are people and places. As long as we can imagine something, it is harder to leave it behind. If we experienced such trauma as children, it becomes infinitely more difficult to overcome the emotional toll of loss as it is so bound up with who we have become.

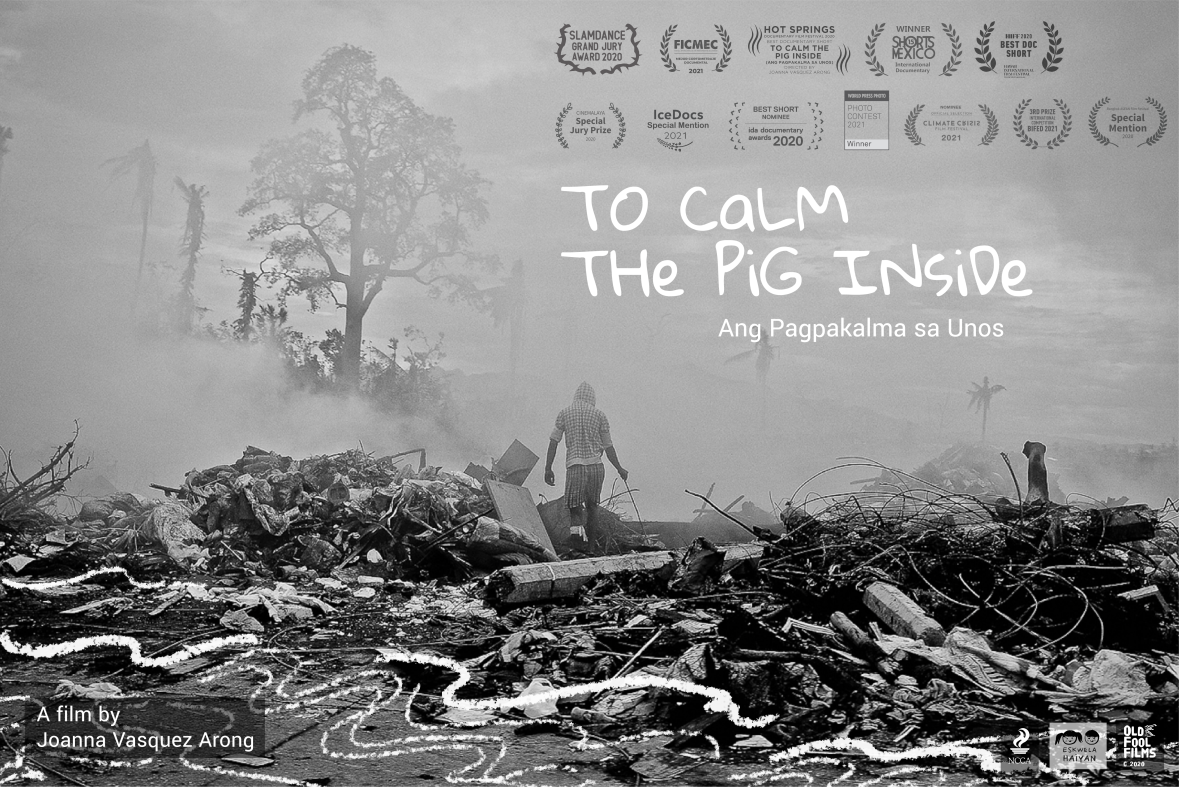

Most people are familiar with fictional movies that deal with such experiences, but what I want to tell you about now is a documentary about an event that occurred in the Philippines in 2013. “To Calm the Pig Inside” is an outstanding short-form documentary written and directed by filmmaker Joanna V. Arong. It focuses on the terrifying impacts of a natural disaster - “Typhoon Haiyan”, also known as Super Typhoon Yolanda - on the coastal city of Tacloban. The title refers to the legend of “buwa”: a pig that lives inside the Earth and that causes earthquakes when it becomes agitated. In times of disaster, the title suggests, people must “calm the pig inside”.

I had the opportunity to watch the film at High and Dry, the Green Film Competition held as part of the Interfilm Festival in Berlin in 2022. Of the seven films, this one affected me the most. Told through the eyes of a little girl, and accompanied by mostly black and white images, the film’s story, visual qualities, and the literary approach used to describe the political and social realities of environmental devastation were simply stunning.

The filmmaker attended the event and spoke briefly before the screening, which was also a great surprise. After watching the film, I knew that I had to contact Ms. Arong and get to know her better; not only because I am writing my Master’s thesis on climate security in the Philippines, but also because she inspired me to consider how I could make my research results more accessible, memorable, and thought-provoking for others, and how I could build up a human connection among people, across generations, and over time through my research.

Typhoon Yolanda struck the Philippines in November 2013 and affected more than 14 million people across 44 provinces, displacing 4.1 million, killing more than 6,000, and leaving 1,800 missing. The typhoon damaged some 1.1 million houses and 33 million coconut trees were damaged or destroyed, creating enormous hardship among affected farmers.

But for me, another striking reality is lost in these facts.

“The dead bodies of the people were lying around the town for weeks,” Ms. Arong explained when we met in Berlin a few days after the screening. The people who survived had to face those dead bodies outside, some of which could not even be identified. This was something that I could not even imagine.

I was shocked that the socio-psychological aspects of this disaster could go unseen for 10 years despite the many news items, articles and academic papers that covered the typhoon.

Behind all those numbers are traumatized individuals with fears, anxieties and frustrations. There are children that must grow up with these experiences while trying to build a future, and families that must find ways to survive despite the disruption in the economic system and the labour and housing markets.

Lives are turned upside down.

But most importantly: there is a society that overcame these challenges through collective sharing, and empathy; through the mutual expression of feelings, frustrations, dreams and, expectations for the future.

I am thankful to Joanna for showing me these moments, especially in one section of the film which grants us insights into the experience of children through drawings. Apparently, sharing these unknown stories with international audiences was one of Joanna’s main goals. She inspired me in many ways before I set out to conduct my fieldwork in the Philippines.

In one review of the documentary, Ricardo Gallegos quotes Guy de Maupassant, who suggested that “Our memory is a more perfect world than the universe. It gives life to people who no longer exist”. He suggests that Joanna gave voice to the underseen – the survivors and children - who sought to restore to life the ghosts that were forgotten by the media and the authorities.

During our meeting with Joanna, she told me that this was her most personal film. “When I saw how this huge, dramatic event affected the community, I had to find a way to understand the devastation. The trauma. And how people were facing it. So I thought of my own personal experience, and decided to frame the film from this personal, subjective perspective.”

“I had heard many of the community's stories as we had launched a scholarship initiative, Eskwela Haiyan, which allowed me to visit the young students we were supporting in the devastated areas twice a year. When I first started meeting with children, I could see which had been the most severely affected – you could also see it in their lives. But I didn’t really ask them what happened. I just said: ‘Here is a piece of paper. You can tell me about it with your drawing.’ These are some of the drawings that made it into the film.”

Watching the film, I could sense this personal connection quite clearly. And it reminded me of something that sociologist Asli Vatansever once noted: “What you do in your research is related to what kind of future you want to see created – maybe more than what kind of past you had. And your vision of the future is – or should be – inspired by your concrete experiences and observations. If you’re not incorporating your own experience into your research, it means that one of them has lost all meaning for you: either your own social reality or your research.”

For me, this bond is among the most crucial elements in creating meaningful research. It is something you feel deep inside that motivates you to better understand the realities you encounter each time and to look for opportunities to contribute to the “change” that we claim to seek.

And if we want change to happen,

we might really need this connection.